Small Strongyles, Larval Cyathostominosis

Parasitic colitis in horses, or larval cyathostominosis, occurs when encysted small strongyle larvae emerge en masse from the intestinal wall, causing inflammation and damaging the mucosa. Unfortunately, anthelmintic resistance is on the rise, creating some difficulties with prophylaxis and treatment of worm burdens. Limitations in the sensitivity and specificity of diagnostic methods can result in parasitic burdens (particularly encysted cyathostomins) being left undiagnosed. The small strongyles are specifically associated with colitis in horses.

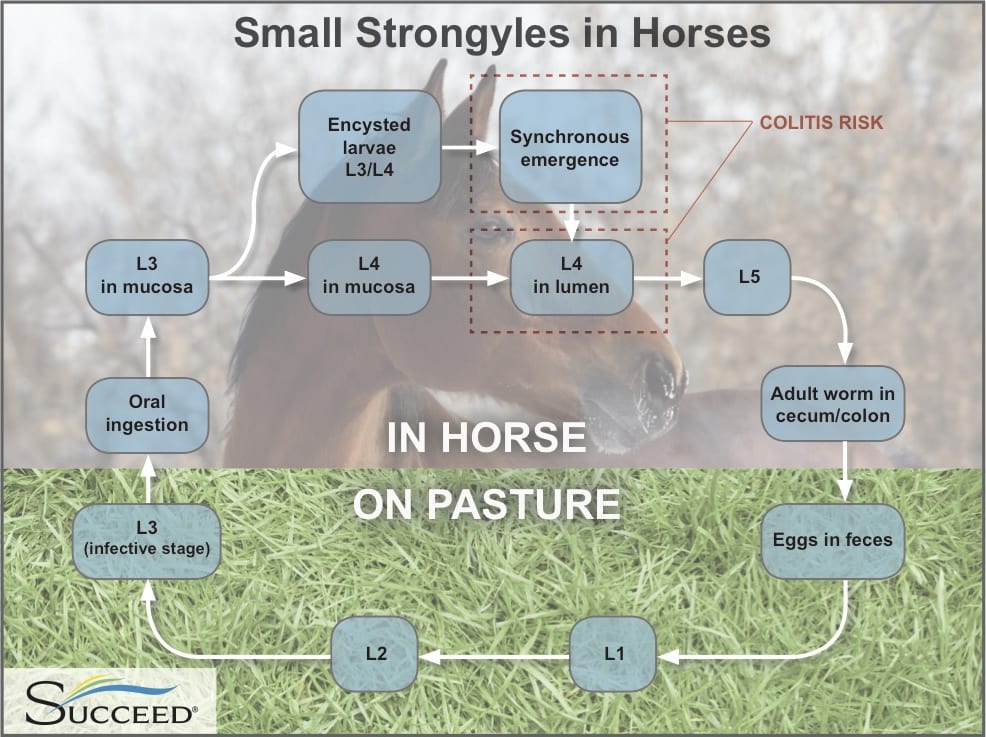

There have been 8 genera and more than 40 species of small strongyles found in the cecum and colon of domesticated horses. They have a direct lifecycle, with eggs being passed in feces and contaminating the pasture. L1 and L2 stages of the lifecycle are pre-infective and environmentally influenced, favoring warm and moist conditions which also reduces the time required for egg hatching. Once ingested, small strongyles in L3 stage will encyst in the cecum and large colon for a minimum of 2-3 months and up to 3 years depending on the species. In this state of hypobiosis they are much less affected by anthelmintic treatment. At some stage (most likely stimulated by climatic conditions) a simultaneous emergence of large numbers of the encysted cyathostomin larvae occurs (L4) and they then migrate back to the lumen of the cecum and colon to continue development into L5 larvae and eventually egg-laying adults. This emergence is referred to as larval cyathostominosis, and is known to cause acute and potentially fatal colitis in horses.

After emergence, the larvae feed superficially on the intestinal mucosa causing disruption and typhlocolitis, which is further exacerbated by areas of local trauma from the remains of evacuated larval pits. Severe cyathostominosis is likely to result in chronic diarrhea, malnutrition, loss of condition, and a cascade of health problems related to colitis and ulceration.

Clinical Signs of Parasitic Colitis in Horses

Larval cyathostominosis tends to be more common in Europe than other regions, and seems to be more prevalent during late winter and early spring. It is also occurs more frequently in horses under the age of six (Mair 1993).

As with any pathology leading to colitis, diarrhea is a near-universal symptom of intestinal inflammation, and is likewise a primary sign of cyathostomin burden.

Other clinical signs may vary in expression and severity depending on the stage of the worm’s life cycle:

- Encysted L3 larval stage: mucosal wall damage may be mild in a light infestation and be localized around each larvae but in a severe burden there may be widespread inflammation with as many as 20-30 nodules/cm2. Disruption to the mucosal lining may result in malabsorption and nutritional deficiencies often reflected in loss of weight, condition and energy, and a delayed shedding of winter coat.

- L4 stage, larval cyathostominosis: Simultaneous emergence stimulates a release of pro inflammatory mediators leading to severe damage to the gut wall. The damaged mucosa may become highly permeable and systemic endotoxemia is likely. This may be overtly characterized by sudden, rapid weight loss (emaciated within 10 days in severe cases), diarrhea (acute, chronic or appears periodically), ventral edema, pyrexia and episodes of colic (cecal intussusceptions and non-strangulating intestinal infarctions).

- In large numbers, adult worms can cause lethargy, sudden weight loss, and debilitation.

Diagnosing Colitis Secondary to Larval Cyathostominosis in Horses

Diagnosing small strongyles as the cause of colitis in horses is challenging, as the syndrome is related to the worm’s larval stage. Thus, fecal egg count is often unhelpful in identifying a small strongyle infection. While strongyle eggs are not often seen on fecal examination, gross observation of the sometimes white but typically bright red L4 or L5 larvae can be helpful. Larvae may be evident in full thickness biopsies of the cecum and colon via celiotomy.

Seasonal, geographical and epidemiological factors may provide an indication, as well as management and anthelmintic history.

A diagnosis of parasitic colitis resulting from larval cyathostominosis should be considered when the horse exhibits weight loss, intermittent diarrhea and unremarkable fecal egg counts. Clinicopathological findings may include hypoproteinemia, hypoalbuminemia, neutrophilia, eosinophilia, elevated beta-globulin levels and less commonly anemia (Love 1992).

Treating Small Strongyles and Colitis in Horses

Larval cyathostominosis unfortunately carries a high risk of fatality. In severe cases successful treatment can be expected in around 40% of horses (Mair 2002). It is not uncommon to observe a short period of recovery, then a rapid decline to death. As with colitis treatment related to any pathology, immediate intensive care is generally standard and includes:

- Anthelmintics,

- Corticosteroids,

- Intravenous fluids to correct fluid and electrolyte loss,

- Plasma transfusions for severe protein loss,

- Anti-endotoxin agents for endotoxemia,

- Analgesics

- Antidiarrheal agents,

- and nutritional support.

These measures may all need to be employed for the severe case and to counteract the cascading effects of colitis.

While the adult worms are easily removed by a wide range of anthelmintics, as long as the population hasn’t developed resistance to the chosen drug, encysted small strongyle larvae are much more difficult to remove. The cysts protect the parasite within the intestinal wall and prohibit the drugs from reaching the larvae.

There are three classes of anthelmintic used in the treatment of small strongyles:

- Benzimidazoles – e.g. fenbendazole and oxfendazole

- Macrocyclic lactones (ML) – e.g. ivermectin and moxidectin

- Tetrahydrophyrimidines – e.g. pyrantel salts

Fenbendazole at recommended doses (5 mg/kg daily for 5 days) has been shown to control adult and developing larval stages of small strongyles and a higher dose (10 mg/Kg daily for 5 days) has been found effective during the encysted stage. However, increasing resistance to fenbendazole among populations is limiting effectiveness and toxicity at higher doses must be cautioned.

While ivermectin is extremely effective for removing small strongyles in adult, luminal larval, and developing stages, it has low efficacy against inhibited stages.

Moxidectin may be the most effective option for small strongyle treatment, as it works against all stages including inhibited larvae, provides ongoing protection against re-infection, and requires less frequent treatment.

Use of pyrantel salts has shown mixed results against adult worms, but shows no effect on inhibited stages.

Note that horses infected with small strongyles may not respond to anthelmintic treatment if submucosal inflammation is too severe, in which case corticosteroids or other supportive therapy are recommended.

If small strongyle infection is effectively removed and colitis responds to treatment, additional steps to aid in full digestive tract recovery are also necessary. Given that varying levels of damage to the digestive tract can occur, it would be prudent in this situation to ensure overall intestinal function is supported throughout treatment and beyond. Clearly, the basic principles of forage-based continual feeding should apply, but promoting a healthy absorptive surface, as well as a stable hindgut environment, should be key targets for intestinal support.

References & Further Reading

- Corning, S. (2009) Equine cyathostomins: a review of biology, clinical significance and therapy

Parasites & Vectors. 2(Suppl 2):S1 - Jasko, D.J., Roth, L. (1984) Granulomatous colitis associated with small strongyle larvae in a horse. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 185(5): 553-4

- Love, S. (1992) Parasite-associated equine diarrhea. Compend Contin Educ Pract Vet. 14: 642–649

- Mair, T.S. (1993) Recurrent diarrhea in aged ponies associated with larval cyathostomiasis. EVJ 25(2):161-3

- Mair, T.S. (2002) Larval cyathostomosis. 432-436. In. Manual of Equine Gastroenterology.

Eds Mair, T.S., Divers, T., Ducharme, N. WB Saunders. Edinburgh, UK

Equine GI Disease Topics

Rooted in science. Supported by research.

From the very beginning, SUCCEED has been developed on a strong foundation of science and research and supported with extensive trials to test performance and clinical value. SUCCEED means science.

Take the next steps toward supporting your practice.

Let’s continue the conversation on equine GI health management. Let us know how we can help.